It’s a question that arises often: should whiskey be spelt with or without the ‘e’?

Geographically, the Irish spelling of whiskey tends to be confined to Ireland and the USA whereas the Scottish spelling of whisky often dominates the rest of the world. There are, of course, outliers in both instances, though where people can slip up is when talking about the origins of the Irish spelling, that being Whiskey… with the ‘e’.

It should be said before anything else that W.D. O’Connell Whiskey are not fussed about the spelling, whether it be whiskey or whisky. What we do care about is education and people understanding the history behind the word. Spelling is irrelevant, it is the truth that matters. The truth about Whiskey.

This is taken from the website for World Whisky Day alongside an article from Hot Rum Cow. While they are a fantastic publication and celebrate the entire world of whiskey, they fall into the same traps when discussing the spelling of whiskey vs whisky – that the spelling is a recent addition in order to differentiate Dublin Whiskey from either Scottish or rural Irish, and one that occurred in the 19th century. They are not the only people to have done this, many, including distilleries here in Ireland and numerous other publications, have fallen into the trap of not fully appreciating what is behind the spelling of Irish Whiskey with an ‘e’.

Let’s be clear, we are not seeking to denigrate, even we have touted incorrect ideas previously as we did not have the knowledge of its history. This blog is about educating those who have an interest in this fantastic industry as to the history of spelling ‘whiskey’ in Ireland and no further.

What we all have missed is this: Irish Whiskey has been spelt with an ‘e’ for centuries and to understand this, we’re going to take a trip through history and etymology.

People are right about one thing, the word whiskey is a recent addition to our vocabulary, though the same is true for the word whisky. Both are derived from the same term and first appear at a similar time in history.

As outlandish as it may seem, many alcoholic drinks share a common etymology, whiskey and whisky belonging to that category. All words have a meaning and the true meaning of whiskey is ‘water of life’. It makes sense when you think about it as whiskey has a life of its own. But, that term is much older than our current spelling as it comes from the old Latin term, ‘Aqua Vitae’, originating around the 14th century.

While this term was used heavily during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and likely has an older history, the term ‘Aqua Vitae’ is used in reference to alcohol derived from the distillation of liquids and spread throughout Europe. In France, it is ‘eau-de-vie’, in Scandinavia, ‘Akvavit’, ‘okowita’ in Poland, and ‘okovyta’ in Russia.

These terms all mean ‘water of life’ and they all sound similar, especially after one or two glasses. When the practice of distillation travelled to Ireland and Scotland, it was no different from the Irish-Gaelic term ‘Uisce Beatha’ and Scottish-Gaelic term ‘Uisge Beatha’. While the spelling is slightly different, most notably Irish Gaelic being spelt with a ‘C’ and Scottish Gaelic using a ‘G’, these terms are intricately linked given the Gaelic history of the countries.

Over the centuries, terms such as ‘Aqua Vitae’ would become antiquated. While the term is used in certain schools of drink, it has disappeared from general conversation. Others, such as the French eau-de-vie and the Scandinavian akvavit, still remain in use – although ‘uisce beatha’ and ‘uisge beatha’ have seen an evolution of the words. We can put this down to colonialism and anglicisation.

Pronouncing words can be tough so words become shortened and change to fit common use and the common tongue. As we can see with our fantastic old Gaelic words, uisce/uisge beatha would turn to something more phonetic, ‘usquebaugh.’ Dropping the ‘beatha’, ‘uisce’ was also used as a solitary word and, through time, the word morphed to whiskey and whisky.

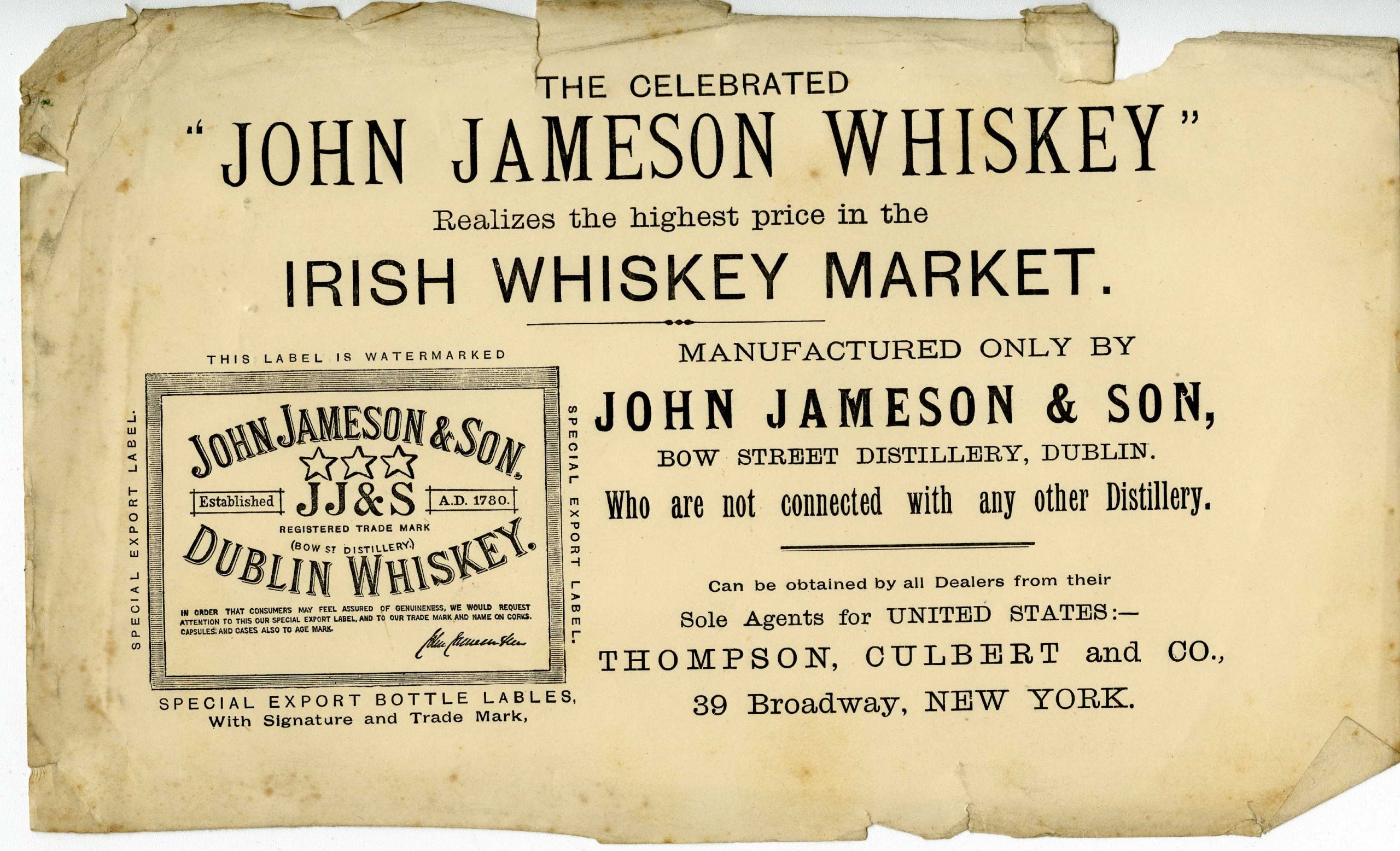

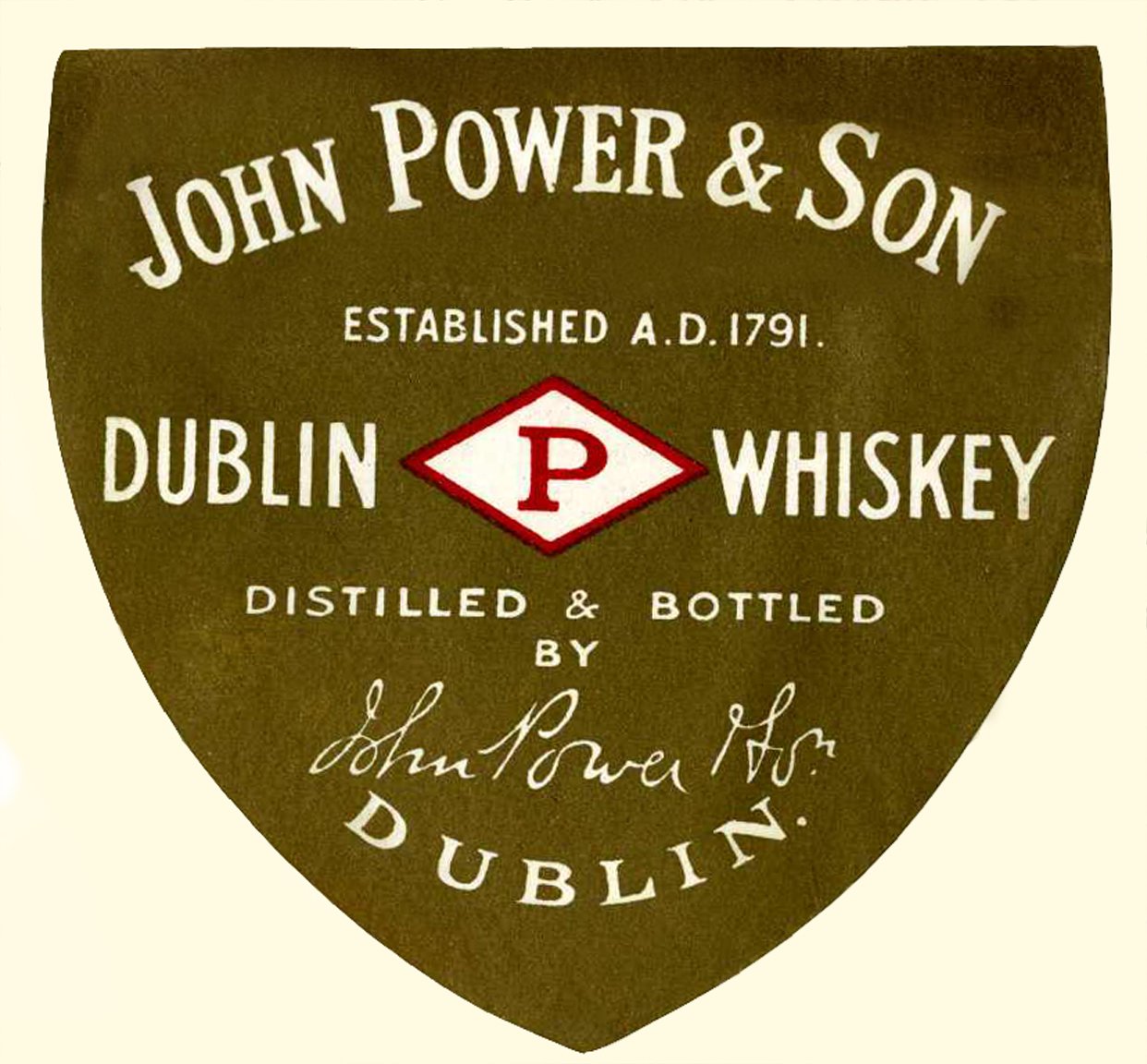

When people talk about the difference in spelling, the point that is often raised is the ‘Truths about Whisky’, a book printed in 1879 by four big distilleries of Dublin at the time: John Jameson & Son, William Jameson & Son, George Roe & Co and John Power & Son. The argument you hear people peddling is that, because the book uses the spelling of ‘whisky’ without the ‘e’, the ‘e’ was only added to the word after the book and, in the early 19th century, in an attempt to differentiate Irish Whiskey from small rural Irish Competition or Scottish Whisky.

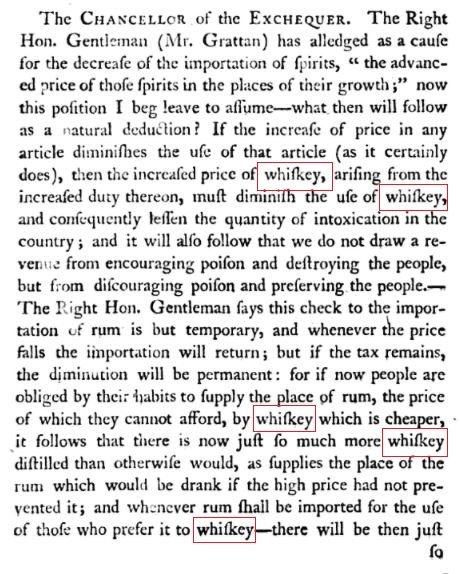

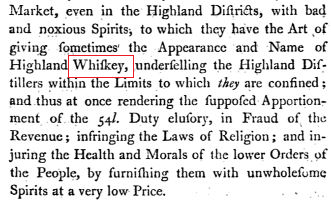

This is simply false – as can be seen from the examples above. Mainly, it is an assumption based on flaws of understanding the writing itself. While, yes, the book does use the spelling ‘whisky’, the sad fact is that this book was not written for an Irish audience. A close inspection of the book reveals that it was published in London and the spelling was most likely decided there without consulting the distillers who wrote it.

So, what is the book about?

The ‘Truths about Whisky’ is the amalgamation of two previous pamphlets, the first published after the testimony of a Mr O’Sullivan in 1876 and the second published the following year, ‘Dublin Whisky, Genuine & Spurious, an account of the frauds practised upon consumers.’ The ‘Truths about Whisky’ would follow from these two pamphlets, all of which were published for international, specifically UK audiences, to alert them to the scams being practised, which were damaging Irish Whiskey.

And so, we come to the ‘Truths about Whisky’ itself, often mistakenly said to be an attack responding to the advent of the Coffey Still patented by Aeneas Coffey. The still could produce a large amount of spirit in a shorter period than a pot still, though, given the size of Irish Distilleries at the time, this was of small concern.

It was problematic and damaging to both simply ship it to and from Dublin bonded warehouses after maturation where it would gain Dublin customs permit, as well as import the silent spirit to the Kings Stores in Dublin and blending it with a small amount of Irish Whiskey. After this, the product could be mislabelled as ‘Dublin whiskey’, while shipping a lesser quality spirit and damaging the name of Dublin and Irish Whiskey.

Hopefully, this can shed some light and dispel notions regarding the book and its formation. Though the book is a valuable resource (despite its harsh words that are driven by what was seen as an affront to the industry), we can dismiss the book as a guide to whiskey spelling.

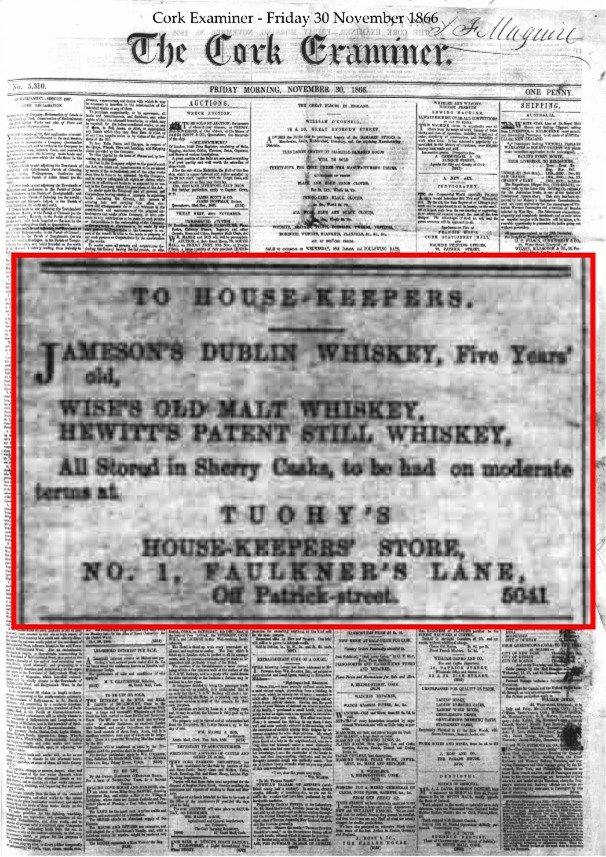

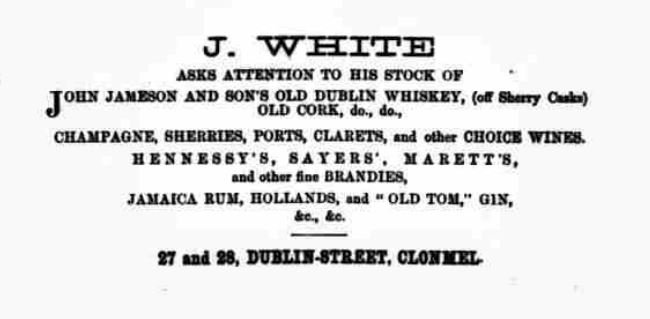

What of the spelling? Well, we know that of the four Dublin distillers, three would spell their product with the ‘e’, (and even William Jameson would label it with the ‘e’ on occasion) before the publication of Truths about Whisky as we can see from the previous examples. Before this, we have examples stretching back near 150 years before the publishing of the Truths about Whisky.

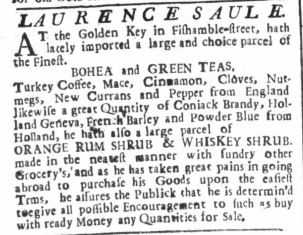

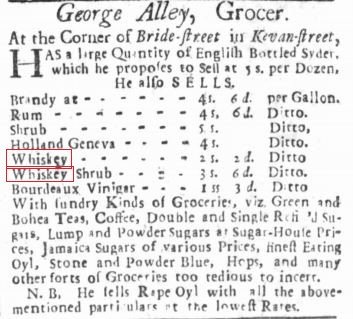

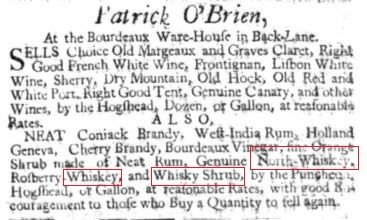

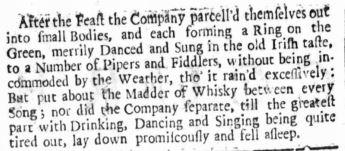

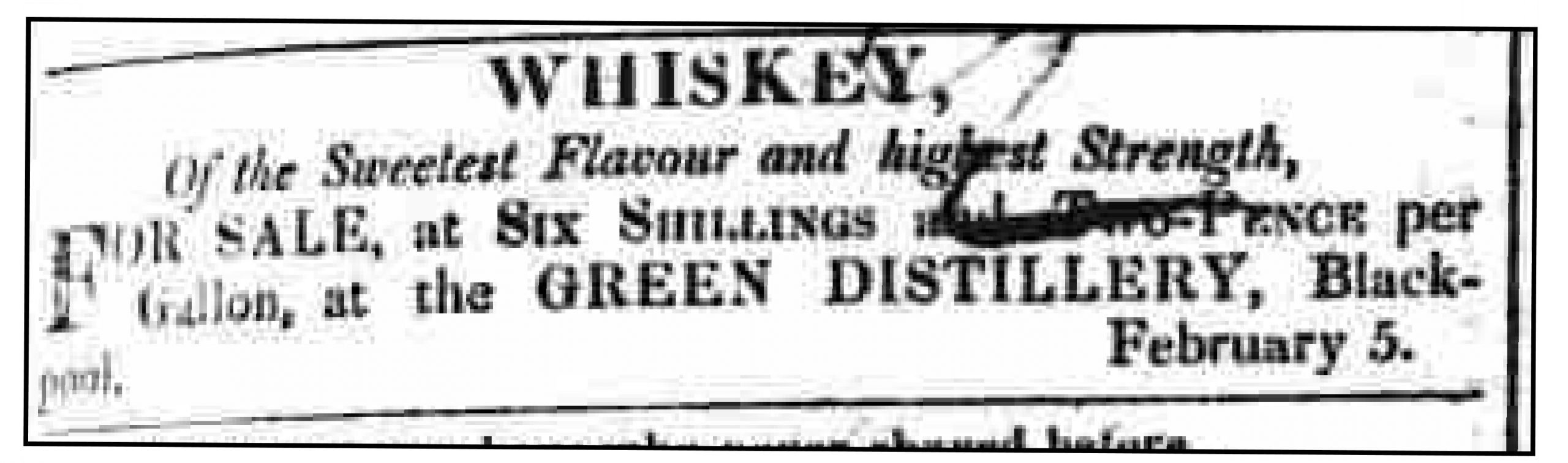

These advertisements from the long running 18th century paper Pue’s Occurences shows the use of the word ‘Whiskey’ as early as 1748 with the use of the word ‘Whisky’ a year later in 1749, though ‘Whiskey’ was clearly the dominant and a trend which would continue through the paper’s publication. The spelling was not confined to a single paper, instances can be found throughout papers in Ireland’s history.

A trio of examples from as early as 1803 show that the much-peddled myth that the Irish added an ‘e’ to their spelling of whiskey to differentiate themselves from the Scottish is just not true, rather a mistake which people should stop repeating. This example also shows the spelling of whiskey in regards to Jameson and Roe Dublin Whiskey – we might speculate that this is George Roe Whiskey.

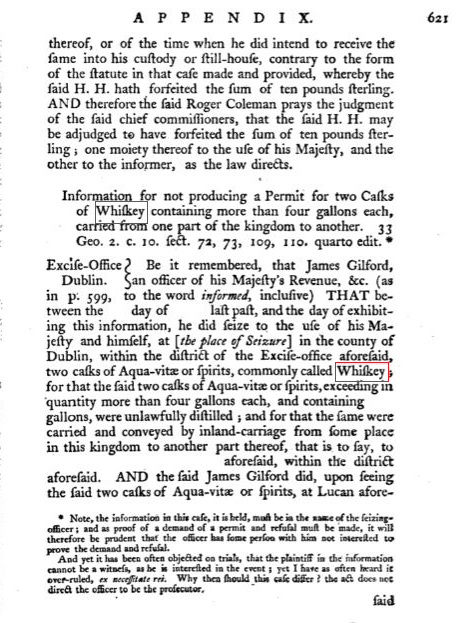

It doesn’t stop there either. In terms of more official wording, whiskey makes its way into numerous documents throughout Ireland and the UK’s parliamentary history, including a report written by Solicitor Gorges Edmond Howard, a report on the transactions of the Irish parliament and a House of Commons report not on Irish distilleries but rather on Scottish Distilleries.

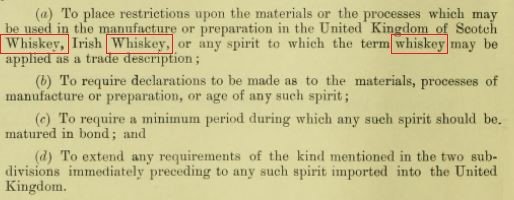

Further solidifying the idea, the Truths about Whisky was followed in 1908 by the Royal Commission on Whiskey and other Potable Spirits. Presented to both Houses of Parliament in 1908, the report sets down maturation restrictions, but also defines both Irish and Scottish whiskey as being spelt with the ‘e’ with almost 6,000 instances of the word written through the report, each in the Irish method.

We even have proof from the distilleries themselves regarding the spelling. Carol Quinn, Head of Archives for Midleton Distillers assures us that the records of John Jameson & Son and John Power & Son were kept within the archive. They have used the spelling of ‘whiskey’ since the beginning.

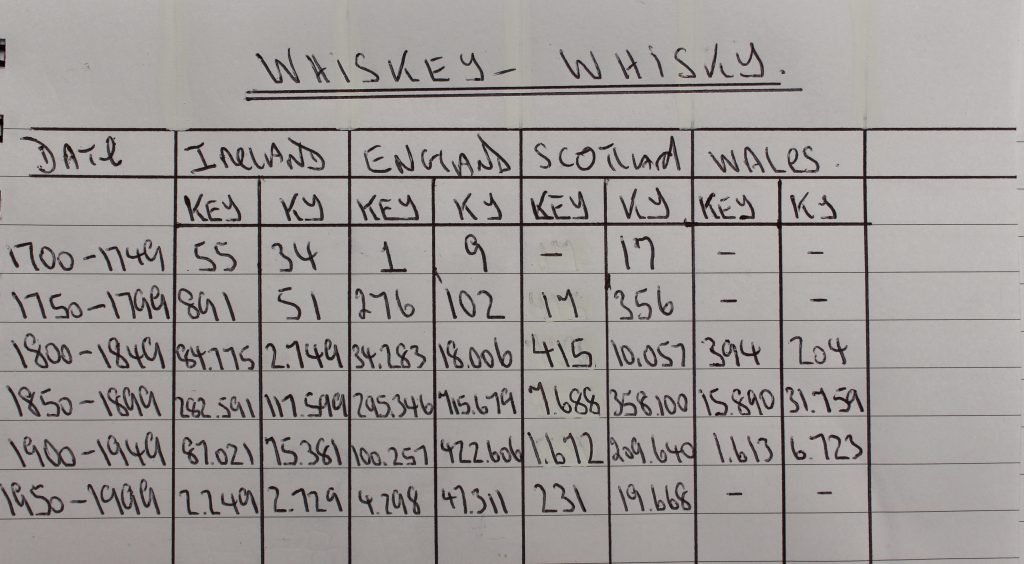

Thus, we have reports, publications, advertisements, and magazine articles from Ireland, Scotland and England, all showcasing the spelling of whiskey both before and after the Truth about Whisky debate. The Dublin Journal, which ran from 1733 to 1825, has 30 instances of the spelling of whiskey, with less than 5 for the spelling of whisky. Research by Charlie Roche reveals that the use of the spelling for whiskey far outweighs the spelling of whisky within National Irish Newspaper, with more than twice the instances of ‘whiskey’ as opposed to ‘whisky’.

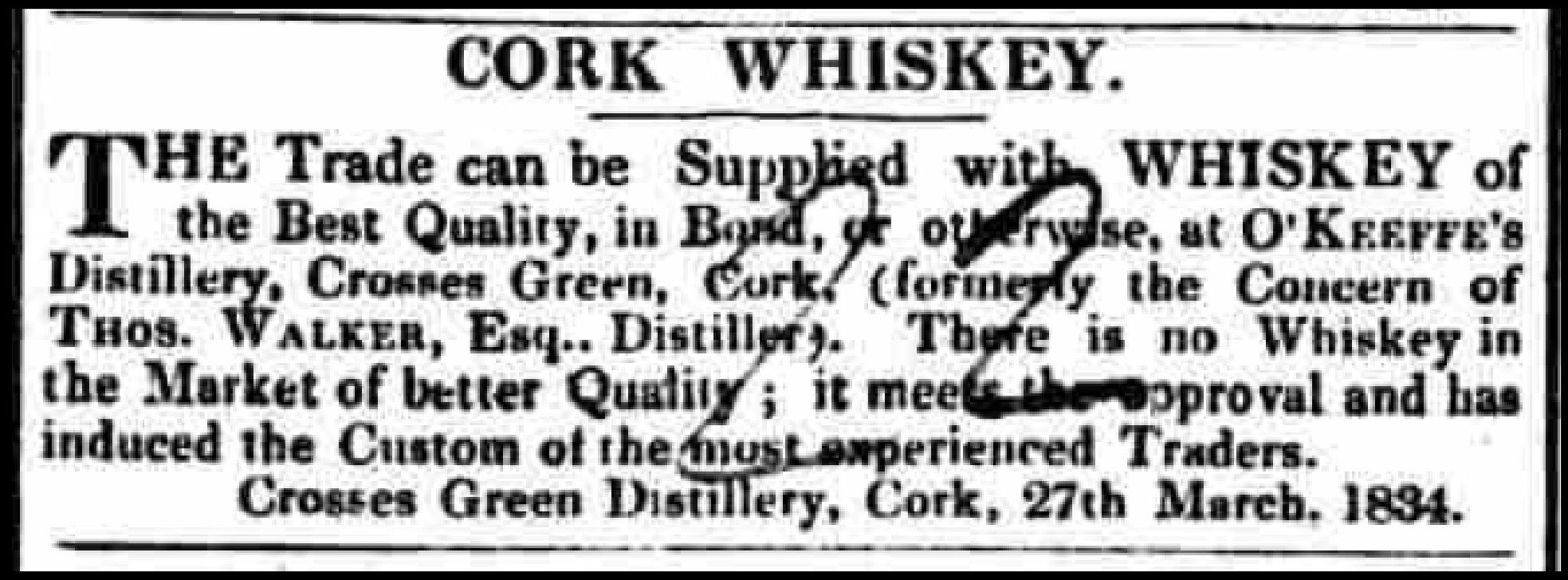

There are examples of outliers in the spelling, such as the Cork Distilleries’ Paddy Whiskey which would use the spelling ‘whisky’ for some years. This example is often given and, again, fails to note that most Cork distilleries would use the spelling of ‘whiskey’, changing after the amalgamation into Cork Distilleries Company in 1867. It would alter its spelling to ‘whiskey’ in the early 1970s but there is proof showing that many Cork Distilleries spelt their product with an ‘e’ in the 19th century.

These examples and more show that it was more common than not when spelling the word whiskey with an ‘e’ through all areas of Ireland. The idea that Irish Whiskey was spelt without the ‘e’ until after 1879 is plainly wrong, as is the idea that the big Dublin Distillers adopted the ‘e’ to differentiate themselves from rural Irish, Cork or Scottish distillers as we have seen that the spelling of whiskey with the ‘e’ was used predominantly throughout all of Ireland.

Unfortunately, Irish Whiskey would soon be met with hard times and such knowledge seemed to fall away.

After the advent of the Coffey Still and the harshly named ‘silent spirit’ it produced, the Irish Whiskey industry would fall into decline. It should be pointed out that it was not solely due to the Coffey Still, the American Prohibition, the First and Second World Wars and the Anglo-Irish Trade War after Irish Independence and arrogance were all factors which would all contribute to the decline of the industry.

In today’s world, the Irish Technical File outlines the rules governing the production of the spirit and makes it clear that, while Irish Distillers are within their rights to label their product as either whiskey or whisky, whiskey is the customary term. This customary spelling is noted in Ireland and around the world as distilleries celebrate their Irish heritage by labelling their product as Whiskey.

In conclusion, we learned that the first appearance of whiskey in Ireland looks like 1748 and 1749 for whisky, both in pues occurrences and that while both lived side by side since then and to this very day Whiskey with the “e” was far more prevalent from 1750 onwards. The pervasive myth that Irish distilleries only added the ‘e’ to differentiate themselves from either small rural distilleries or Scottish distilleries, is a false assumption. Almost three centuries ago, we had examples of the spelling and can only assume that hundreds – if not thousands – more examples must have been lost through time. Far from being a recent addition, both the words whiskey and whisky seem to have evolved and come into the language at the same time.

What now? It seems the answer is obvious, sit down with a glass of whiskey and wonder what myth we can rid the whiskey world of next.

###

Writing this article would have been impossible without the contribution and help of Charlie Roche, an Irish Whiskey historian whose value to Irish Whiskey should not be taken for granted, míle buíochas Charlie. Additional thanks to Carol Quinn, Head of Archives for Irish Distillers Pernod Ricard for her time and assistance.

If you liked what you read and the evidence compels you to share this with your friends in the wider whiskey community please do so, and we can all start singing from the same accurate hymn sheet.

This article was written on behalf of W.D. O’Connell Whiskey Merchants by Marcus Parmenter, better known within the whiskey world as Somewhiskybloke. You can read more from Marcus on his website Somewhiskybloke.com though he does tend to ramble.

Sláinte,

Bibliography/References

1 Liz Long den (2014), ‘A brief, but cask strength, history of whisky’ Hot Rum Cow (Issue 3) May 24th

2 (1866) The Cork Examiner

3 Old Jameson export labelling 1869, courtesy of IDL Archives

4 (1870) Clonmel Chronicle

5 Old Powers Gold Label 1886, courtesy IDL Archives

6 (1748) Pue’s Occurences, Wednesday 28th December

7 (1749) Pue’s Occurences, Tuesday 20th June

8 (1749) Pue’s Occurences, Tuesday 7th November

9 (1749) Pue’s Occurences, Tuesday 8th August 1749

9 (1803) Saunder’s News-Letter, Thursday 13th January

10 (1827) Southern Report and Cork Commercial Chronicle, Saturday 3rd February

11 (1858) The Irishman, Saturday 6th November

12 Gorges Edmond Howard (1779), An Abstract and Common Place of all the Irish, British and English Statutes

Relative to the Revenue of Ireland and the Trade connected Therewith, p. 621

13 (1792) Transactions of the Parliament in Ireland, p. 69

14 S. Gosnell (1798), Reports Respecting The Distilleries In Scotland, p. 9

15 (1908) Royal Commission on Whiskey and other Potable Spirits, p. 8

16 Charlie’s findings on the spelling of Whiskey vs Whisky through Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales

17 (1831) Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Chronicle, Tuesday 15th February

18 (1834) Cork Constitution, Saturday 29th March

SHARE THIS POST